09A terminations of grants provided by entry into new copyright term

About This Page

This page contains the following subsections:

09A.1 — renewal term: derivative-version rights (go there)

09A.2 — renewal term: rights of widows, widowers and next-of-kin (go there)

Where to Look in the Law

1909 Act: §23

1947 Act: §24

1976 Act: §304(c), §203 (grant terminations)

Copyright Office Publications for Laymen

“For works already under statutory copyright on January 1, 1978, the law also contains special provisions allowing the termination of any grant of rights made by an author and covering any part of the period (usually 39 years) that has now been added to the end of the renewal copyright. This right to reclaim ownership of all or any part of the extended term is optional. It can be exercised only by certain persons (the author, or specified heirs of the author), and it must be exercised in accordance with prescribed conditions and within strict time limits.” (Information Circular 15t)

Concerning “Copyrights secured between January 1, 1964, and December 31, 1977[:] The amendment to the copyright law enacted June 26, 1992, makes renewal registration optional, and the amendment enacted October 27, 1998, further extends the renewal term to 67 years. The copyright is still divided between a 28-year original term and a 67-year renewal term, but the renewal term automatically vests on December 31st of the 28th year. A renewal registration is not required to secure the renewal copyright. Certain benefits accrue to making renewal registrations, and the Copyright Office continues to accept renewal applications.” (Information Circular 15t)

What the Supreme Court Ruled

Fred Fisher Music Co. vs M. Witmark & Sons

318 U.S. 643 (4-5-1943)

Ernest R. Ball, Chauncey Olcott, and George Graff, Jr. wrote the popular song “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” in 1912. Each songwriter was under contract to music publisher M. Witmark & Sons. On August 12, 1912, Witmark registered copyright. This gave the song a 28-year first-term copyright, eligible for renewal between August 12, 1939, and August 12, 1940. On May 19, 1917, Graff and Witmark made a further agreement whereby for $1600, Graff assigned to Witmark “all copyrights and renewals of copyrights” in several songs, including “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling.” (This included all rights he and his “heirs, executors, administrators or next of kin may at any time be entitled to.”) On August 12, 1939, Witmark filed for the renewal. Graff did likewise on August 23, 1939, and on October 24, 1939, Graff assigned his renewal interest to Fred Fisher Music Co. Fisher then published and offered their own copies of “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling,” prompting Witmark to obtain an injunction. Fisher and Graff contended that Graff’s 1917 sale of renewal rights were void because the intention behind the 1909 law was that authors not sell their renewal rights until the renewal term began. The Supreme Court ruled that “an agreement to assign his renewal, made by an author in advance of the twenty-eighth year of the original term of copyright, is valid and enforceable”. The Court observed: “The explicit words of the statute give the author an unqualified right to renew the copyright. No limitations are placed upon the assignability of his interest in the renewal.”

The Court recognized that authors might sell their renewal rights for less than the value yet that it is the author’s choice to do so and that the alternative ruling would put an end to there being buyers for future rights. “If an author cannot make an effective assignment of his renewal, it may be worthless to him when he is most in need. Nobody would pay an author for something he cannot sell.” (Oddly enough, Ball and Olcott, the two other authors of the song, are not mentioned in the ruling insofar as renewal assignments are concerned.)

Miller Music Corp. vs Charles Daniels, Inc.

362 U.S. 373 (4-18-1960)

Ben Black and Charles Daniels composed the song “Moonlight and Roses” (1925) and assigned it to Villa Moret, Inc., which secured the original copyright. Prior to the expiration of the 28-year term, Black assigned to Miller Music Corp. his renewal rights in this song in consideration of certain royalties and the sum of $1,000. Black’s next of kin were three brothers. Each of them executed a like assignment of his renewal expectancy and delivered it to Miller. These assignments were recorded in the Copyright Office. Before the expiration of the original copyright, Black died, leaving no widow or child. His will contained no specific bequest concerning the renewal copyright. His residuary estate was left to his nephews and nieces. One of the brothers qualified as executor of the will and renewed the copyright for a further term of 28 years. The probate court decreed distribution of the renewal copyright to the residuary legatees. Daniels, Inc. then obtained assignments from them. The Supreme Court weighed the different executors, testators, and heirs of different degree. It decided, “The category of persons entitled to renewal rights therefore cannot be cut down and reduced as petitioner would have us do.” Prior to death of the creator, “assignees of renewal rights take the risk that the rights acquired may never vest in their assignors.” Thus, “where the author dies intestate prior to the renewal period leaving no widow, widower, or children, the next of kin obtain the renewal copyright free of any claim founded upon an assignment made by the author in his lifetime. These results follow not because the author’s assignment is invalid but because he had only an expectancy to assign; and his death, prior to the renewal period, terminates his interest in the renewal”. (Four Supreme Court justices dissented, one writing “the assignee of an author’s renewal rights in a copyrighted work is deprived of the fruits of his purchase[… .] While, for all that appears, the author in this case may not have contemplated the defeat of his assignment, the effect of the decision is to enable an author who has sold his renewal rights during his lifetime to defeat the transaction by a deliberate subsequent bequest of those rights to others in his will.” Quite apart from whether this is a sound argument, the policy it would lead to is the opposite of what would be followed by subsequent courts.)

(EDITOR’S NOTES: In looking up records for Charles V. Daniels, realize that he was in fact named Neil Moret. “Moonlight and Roses” was based on Edwin H. Lemare’s Andantino in D-flat (1892).)

Mills Music, Inc. vs Snyder

469 U.S. 153 (1-8-1985)

Ted Snyder was one of three persons who collaborated in creating the song “Who’s Sorry Now.” Copyright was registered in 1923 in the name of Waterson, Berlin & Snyder Co. (of which Snyder was part owner). (The other two owners can be ignored insofar as this case is concerned, owing to mutual agreement.) After that company’s bankruptcy in 1929, the trustee assigned the copyright to Mills Music, Inc. in 1932. “Although Mills had acquired ownership of the original copyright from the trustee in bankruptcy, it needed the cooperation of Snyder in order to acquire an interest in the 28-year renewal term. Accordingly, in 1940 Mills and Snyder entered into a written agreement defining their respective rights in the renewal of the copyright. In essence, Snyder assigned his entire interest in all renewals of the copyright to Mills in exchange for an advance royalty and Mills’ commitment to pay a cash royalty on sheet music and 50 percent of all net royalties that Mills received for mechanical reproductions. Mills obtained and registered the renewal copyright in 1951.” Mills licensed rights to make 400 recordings (different artists, different companies) and Snyder received his percentage. After his death, Snyder’s widow and son received the royalties. The 1976 Copyright Act gave the Snyders a “third” term of a sort (a 19-year extension) and the right to terminate agreements at the end of the current term. However, “a previously prepared derivative work” could “continue to be utilized after the termination ‘under the terms of the grant.’”

The Supreme Court decision summarized the problem in this way: “This is a controversy between a publisher, Mills Music, Inc. (Mills), and the heirs of an author, Ted Snyder (Snyder), over the division of royalty income that the sound recordings of the copyrighted song ‘Who’s Sorry Now’ have generated. The controversy is a direct outgrowth of the general revision of copyright law that Congress enacted in 1976. The 1976 Act gave Snyder’s heirs a statutory right to reacquire the copyright that Snyder had previously granted to Mills; however, it also provided that a ‘derivative work prepared under authority of the grant before its termination may continue to be utilized under the terms of the grant after its termination.’ The sound recordings of the song, which have generated the royalty income in dispute, are derivative works of that kind. Thus, the dispute raises the question whether an author’s termination of a publisher’s interest in a copyright also terminates the publisher’s contractual right to share in the royalties on such derivative works.

“The key that will unlock this statutory puzzle is an understanding of the phrase ‘under the terms of the grant’ as it is used in 304(c)(6)(A) — the so-called ‘derivative works exception’ to the ‘termination of transfer and licenses’ provisions found in 304(c)”.

The District Court noted that the statute did not make “any distinction between grantees who themselves make or own derivative works and those who license others to do so.” Mills fell into a gray area. The answer would make the difference as to whether Mills would continue to receive a percentage on future sales of recordings that it had licensed during its proprietorship of the song or whether the Snyders would get all of the royalties. Mills was certainly not an “author,” yet if it could be shown it was a “utilizer,” its rights in prior grants would be upheld. Being found a publisher would work against them (tantamount to being “other noncreative middlemen”). The Supreme Court determined that it was Snyder’s 1940 “grant” to Mills that Mills used to issue “grants” to record companies, and thus the subsequent licenses for 400-odd recordings were “under authority of the grant.”

Stewart vs Abend

495 U.S. 207 (4-24-1990)

“For works existing in their original or renewal terms as of January 1, 1978, the 1976 Act added 19 years to the 1909 Act’s provision of 28 years of initial copyright protection and 28 years of renewal protection. See 17 U.S.C. 304(a) and (b). For those works, the author has the power to terminate the grant of rights at the end of the renewal term and, therefore, to gain the benefit of that additional 19 years of protection. See 304(c). In effect, the 1976 Act provides a third opportunity for the author to benefit from a work in its original or renewal term as of January 1, 1978. Congress, however, created one exception to the author’s right to terminate: The author may not, at the end of the renewal term, terminate the right to use a derivative work for which the owner of the derivative work has held valid rights in the original and renewal terms. See 304(c)(6)(A). The author, however, may terminate the right to create new derivative works. Ibid. For example, if petitioners held a valid copyright in the story throughout the original and renewal terms, and the renewal term in Rear Window were about to expire, petitioners could continue to distribute the motion picture even if respondent terminated the grant of rights, but could not create a new motion picture version of the story.”

(A thorough summary of this case is under renewal term: derivative-version rights.)

What the Lower Courts Ruled

G. Ricordi & Co. vs Paramount Pictures

C.A.N.Y. (5-8-1951) ¤ 189 F.2d 469, certiorari denied 72 S.Ct. 77, 342 U.S. 849, 96 L.Ed.

“A copyright renewal creates a new estate and … the new estate is clear of all rights, interests or licenses granted under the original copyright.”

After 1945, both plaintiff and defendant were “free to use the play” owing to expiration.

(A more complete summary of this case is under underlying copyright.)

|

illustration: timeline chart of copyright status on various versions of Madame Butterfly.

Easton vs Universal

Supreme Court, N.Y.Co. (3-26-1968) ¤ 288 NYS.2d 776

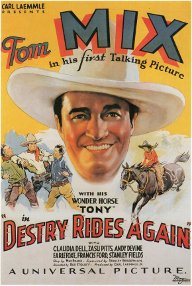

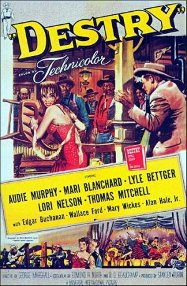

The widow of the author the Western novel Destry Rides Again (1930) assigned her 50% right to a bank, which in 1952 assigned its right to Universal Studios for $4500. Universal had made two movie versions under that title, including a famous 1939 version as well as a less-remembered 1932, in addition to 1950 and 1954 versions under other titles (Frenchie and Destry, respectively), so Universal had a stake in securing the rights to the renewal term of the underlying work. The three children of the author held the other 50% of the rights, and they seemingly also transferred their rights. Universal renewed the story in 1956. The widow then died and in May 1960 the children asserted that the bank trust had only obtained the widow’s rights, not the 50% they owned. The Court ruled that when the sale of the movie rights for the first term had occurred in 1931 it had been for $1650, the equivalent of which after devaluation was about $4500 decades later, so that had been the fair price for the rights for the second term. illustrations: posters for (top to bottom, then left to right) the 1932, 1939, 1950 and 1954 film versions of Destry Rides Again. | ||||

| ||||||||||

Trust Company Bank, as Trustee for Eugene Muse Mitchell and Joseph Reynolds Mitchell under Trust Instruments dated November 5, 1975, and Trust Company Bank, as executor of deceased Stephens Mitchell vs MGM/UA Entertainment Company

USCA, 11th Cir. (9-27-1985) ¤ 772 F.2d 740

This case concerned disagreement over language in contracts for Gone With the Wind that could be read to either allow or not allow the movie studio owning the movie to make sequels. (As the matter came down to deciphering the intended meaning in contract language, the decision rested on something other than the application of copyright law per se, and thus is not within the scope of this web site. The decision does make reference to the precedent set in Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc. v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc. (1954), discussed in this web site under rights to create derivative versions.)

|

|

Of relevance to the subject of renewal-term rights is the matter in the following quote. (It begins in the next paragraph). The legal principles discussed were not disputed by any of the parties when the actions were taken from 1961 to 1963, nor was there a dispute over these particular principles when litigation over the sequel rights occurred two decades later. The 1936 agreement mentioned is the one in which Margaret Mitchell sold the movie rights to her one novel, Gone With the Wind, to Selznick International Pictures, Inc. (SIP).

“In the 1936 agreement, Ms. Mitchell had agreed to renew the copyright to Gone With the Wind prior to expiration of the original copyright in 1963 and that SIP would have rights in the novel during the renewal copyright period. However, under settled law, her estate was relieved of that contractual obligation because Ms. Mitchell died before the initial term of copyright expired. To retain motion picture rights in Gone With the Wind after the original copyright expired in 1963, MGM, as successor-in-interest to SIP, had to obtain a grant of renewal rights from Stephen Mitchell [the author’s brother], in whom such rights were vested in the early 1960s. MGM was, obviously, anxious to obtain this renewal, since Gone With the Wind was one of its most valuable properties, if not its most valuable property.

“MGM and Stephen Mitchell, through their representatives, commenced negotiations for the grant of renewal rights in January 1961. Negotiations lasted thirty months, culminating in May 1963 with the execution of a written agreement dated December 4, 1961. [It] provided that MGM was to receive ‘[a]ll the same rights under renewal copyright as were granted to SIP under the [1936 agreement]… .’”

(EDITOR’S NOTE: What these negotiations indicate is that it was established policy among major Hollywood studios to negotiate anew for renewal-term rights when the author of an underlying work died during the initial 28-year term of copyright in the underlying work. News accounts at the time of the “Rear Window decision” (Stewart v. Abend, 1990) would have readers believe that the 1990 decision had thrown Hollywood into a disarray over an application of law that movie-makers previously had not understood. The negotiations between MGM and Margaret Mitchell’s heir substantiate evidence of the opposite view.)

(Incidentally, the decision in Trust Company Bank v. MGM/UA decided that MGM/UA did not own any rights to create a sequel, as none had been granted to Selznick (predecessor-in-interest to MGM and MGM/UA) nor had any been gained by MGM in 1963 in the agreement covering the renewal term of the underlying work to the existing movie.)

P.C. Films Corp. vs MGM/UA Home Video Inc., MGM/UA Communications Co., Warner Home Video, Inc., Turner Entertainment Co.

USCA 2nd Cir. (2-23-1998) ¤ 138 F.3d 453, No. 97-7399

P.C. Films acquired the rights to the film King of Kings (1961) held by Samuel Bronston Productions upon Bronston’s bankruptcy in 1967. King of Kings had been made after Bronston and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc. entered an agreement August 4, 1960, providing for “the production, financing and distibution of the film.” “Turner Entertainment Co. is the successor in interest to MGM… . Warner Home Video… is distributing the film in home video pursuant to licenses obtained from Turner.” P.C. Films contended that after the first term of copyright ended (in 1989), MGM’s exclusive right to distribute the film should have ended and P.C. Films should have the right to negotiate distribution arrangements anew. The Court found that, “The Basic Agreement does not expressly refer to rights in the renewal period. However, the Basic Agreement granted MGM the ‘perpetual and exclusive right to distribute the film.” The Court supplied a dictionary definition of “perpetual” which supported the view that this meant “forever”. Further, “the testimony of the sole surviving participant in the negotiations, MGM’s Vice President and General Counsel,” was that “MGM would not have financed the picture for less than a perpetual term”. The Court recognized the precedent of Miller Music Corp. v. Charles N. Daniels. The P.C. Films decision recognizes that the renewal term is a “new estate… clear of all rights, interests or licenses granted under the original copyright” (quoting Ricordi), but also that “[t]he Supreme Court has consistently allowed authors to assign their rights in the renewal term before that term commences.” The critical point: “Under copyright law, where a contract is silent as to the duration of the grant of copyright rights, the contract is read to convey rights for initial copyright period only.” Here, “the Basic Agreement can be lawfully interpreted to continue through the renewal period”. (Given the opposing views as to which firm was entitled to rights in the renewal term, it’s not surprising that there were two renewal registrations. This is discussed in renewal registration rights.) (EDITOR’S NOTE: The decision never discusses whether the bankruptcy of Samuel Bronston Production could be compared to a death in the legal sense and thus cause the second term of copyright to become a “new estate”. Other statutes in American law establish differences between persons and corporations insofar as each being a legal entity with oblibations and privileges. In that there wasn’t a death of the original author of this film, the decision in this case follows precedent.) Other Information“[N]otwithstanding a termination, a derivative work prepared earlier may ‘continue to be utilized’ under the conditions of the terminated grant; the clause adds, however, that this privilege is not broad enough to permit the preparation of other derivative works. In other words, a film made from a play could continue to be licensed for performance after the motion picture contract had been terminated but any remake rights covered by the contract would be cut off. For this purpose, a motion picture would be considered as a ‘derivative work’ with respect to every ‘preexisting work’ incorporated in it, whether the preexisting work was created independently or was prepared expressly for the motion picture.” Quotation of H. R. Rep. No. 94-1476, at 127, quoted in full within the judgment of Shoptalk v. Concorde-New Horizons, 168 F.3d 586 (2d Cir. 1999). Congress had been moved, in revising the copyright laws for the 1909 Act, by some difficulties encountered by Mark Twain, who by the early 20th century was a fantastically successful author and speaker but had achieved his fame after enduring a struggle, as he related to Representative Currier, the chairman of the House committee, who in turn spoke of this during the hearings of the Joint Committee: “Mr. Clemens [Twain’s real name] told me that he sold the copyright for Innocents Abroad for a very small sum, and he got very little out of the Innocents Abroad until the twenty-eight year period expired, and then his contract did not cover the renewal period, and in the fourteen years of the renewal period he was able to get out of it all of the profits.” (Hearings before the Committees on Patents of the Senate and House of Representatives on Pending Bills to Amend and Consolidate the Acts respecting Copyright, 60th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 20.) 09A.1 renewal term: derivative-version rights Where to Look in the Law1909 Act: §23 Copyright Office Publications for LaymenCircular 14 What the Supreme Court RuledStewart vs Abend495 U.S. 207 (4-24-1990)In 1945, author Cornell Woolrich agreed to assign the motion picture rights to several of his stories, including It Had To Be Murder (1942), to B. G. De Sylva Productions. He also agreed to renew the copyrights

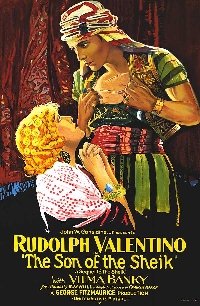

The Supreme Court grappled with whether the movie owners had indeed secured a contractual obligation from Woodrich that he or his heirs would fulfill the renewal assignment or whether no such obligation was borne by the heir. The Court was moved in favor of Abend in that, “most important, the record supports the conclusion that re-release of the film impinged on Abend’s ability to market new versions of the story.” The Court found precedent in previous Supreme Court decisions concerning renewal rights: • “assignees of renewal rights take the risk that the rights acquired may never vest in their assignors. A purchaser of such an interest is deprived of nothing. Like all purchasers of contingent interests, he takes subject to the possibility that the contingency may not occur.” (quoted from Miller Music Corp. v. Charles N. Daniels, Inc., 362 U.S. 373 (1960)) • “The evident purpose of [the renewal provision] is to provide for the family of the author after his death. Since the author cannot assign his family’s renewal rights, [it] takes the form of a compulsory bequest of the copyright to the designated persons.” (quoted from De Sylva v. Ballentine, 351 U.S. 570, 582 (1956)) • “A derivative work prepared under authority of the grant before its termination may continue to be utilized under the terms of the grant after its termination, but this privilege does not extend to the preparation after the termination of other derivative works based upon the copyrighted work covered by the terminated grant.” (quoted from 304(c)(6)(A) of the 1976 Act) (emphasis added by Court). “Congress would not have stated explicitly in 304(c)(6)(A) that, at the end of the renewal term, the owner of the rights in the pre-existing work may not terminate use rights in existing derivative works unless Congress had assumed that the owner continued to hold the right to sue for infringement even after incorporation of the pre-existing work into the derivative work. Cf. Mills Music, Inc. v. Snyder, 469 U.S. 153, 164 (1985) (304(c)(6)(A) ‘carves out an exception from the reversion of rights that takes place when an author exercises his right to termination’).” The Court recognized that the decision it was making would hinder the public’s access to previously-available works, yet it said that the Copyright “Act creates a balance between the artist’s right to control the work… and the public’s need for access… But nothing in the copyright statutes would prevent an author from hoarding all of his works during the term of the copyright. In fact, this Court has held that a copyright owner has the capacity arbitrarily to refuse to license one who seeks to exploit the work. See Fox Film Corp. v. Doyal, 286 U.S. 123, 127 (1932).” What the Lower Courts RuledRaymond Rohauer vs Paul KilliamUSDC SDNY (8-8-1974) ¤ 379 F.Supp. 723Raymond Rohauer and Cecil Hull vs Killiam Shows and Educational Broadcasting Corp.USCA 2nd Cir. (1-7-1977) ¤ 551 F.2d 484, 192 USPQ 545Edith Maude Hull wrote the novel The Sons of the Sheik, the basis of a film starring the highly-popular Rudolph Valentino. (The film title uses the singular Son in place of the plural Sons). Ownership of the film had been bought by Paul Killiam of Killiam Shows. The son of the author, Cecil Hull (confined to a nursing home since 1969), granted his rights to Raymond Rohauer, who said that no rights were provided to Killiam for a television showing of the film on July 13, 1971. The picture had been shown often on TV since 1960. Rohauer had been responsible for numerous showings in theaters from 1952 to 1965, having bought a print from Art Cinema Association, which didn’t sell its interests to Killiam until 1961. “Nineteen years elapsed between 1952, the year Cecil Hull renewed copyright to The Sons of the Sheik and 1971, the year this action was commenced. During that interval the motion picture was shown frequently on television in both Great Britain [Hull’s country] and the United States, but at no time did either Cecil Hull (prior to 1965) nor Rohauer (after 1965) raise any objection or make any attempt to restrict the motion picture’s exhibition. … Nor is there any evidence that either Cecil Hull or Rohauer intended their inaction to permit those such as defendant to show the motion picture without authorization.”

On appeal, the Court considered language in the agreements made before the film was produced. The assignment explicitly covered the renewal term. “Where author of copyrighted story assigned purchaser motion picture rights and consented to purchaser’s securing copyright on motion picture version, and terms of assignment demonstrated intent that rights of purchaser would extend through renewal of copyright on story, and where assignee of purchaser and its successors made film and obtained derivative and renewal copyright thereon, it did not infringe renewal copyright on story for successor of assignee of purchaser to authorize performance of film after author had died and copyright on story had been renewed by author’s statutory successor, who had made new assignment of motion picture and television rights.” Thus, the earlier verdict was reversed. The Judge in his decision indicated several factors which prejudiced the case against Rohauer. He mentions Rohauer’s “refusal to submit to discovery” in an “Iowa case”. (Although no names are mentioned, this almost certainly concerned an action by Rohauer against Eastin-Phelan Corp. [a.k.a. Blackhawk Films], which contracted with Killiam to offer film prints sold to libraries and collectors.) Further, Rohauer had exhibited the film prior to 1965 without any license from Hull, so thus had engaged in the same trampling of the film’s underlying rights which he then used against Killiam. EDITOR’S NOTE: For the reasons mentioned in this paragraph, readers might want to place more weight on the verdicts in similar cases, particularly Abend. A good summary of the finding was written a few years later: “The precise holding in Rohauer was that a derivative copyright proprietor who had been promised a reconveyance on his license rights upon renewal of the underlying copyright, could enforce that promise as against the statutory successors of the deceased proprietor inherent in the underlying copyright except to the limited extent that a right of derivative use had been granted the licensee.” (Quotation from Filmvideo Releasing Corp. v. David R. Hastings [for the Estate of Clarence E. Mulford], USCA 2nd Cir. (12-11-1981), 668 F.2d 91.) 09A.2 renewal term: rights of widows, widowers and next-of-kin Where to Look in the LawSee above Copyright Office Publications for LaymenCircular 15 What the Courts RuledVon Tilzer vs Jerry Vogel Music Co.D.C.,S.D.N.Y. (10-5-1943) ¤ 53 F.Supp. 191, affirmed 158 F.2d 516.Harry Von Tilzer composed the song “Down on the Farm” (lyrics by Raymond A. Browne, at least in part), which was copyrighted July 26, 1902, by Harry Von Tilzer Music Publishing Co. Tilzer renewed on July 16, 1930. Lyricist Browne had been on fixed salary to Tilzer, and had received no other compensation through his death on May 9, 1923. Had Browne been entitled to half the copyright, his death would have given his widow rights in the second term. However, because Browne worked on a work-for-hire basis, Vogel’s claim of having rights by means of an assignment from Browne’s widow, was not grounded. (The dispute in the same trial over the rights in another song, is summarized under renewal registration rights.) Peter Bartok vs Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. and Benjamin Suchoff, as Trustee of the Estate of Bela BartokUSCA 2nd Cir (9-26-1975) ¤ 523 F.2d 941, 187 USPQ 529Classical music composer Bela Bartok (died 1945) executed a contract for a composition (Concerto for Orchestra) and its copyright, and later corrected the proofs of the sheet music, but he died before tangible copies were made available for sale. The composition was performed during Bartok’s lifetime but not “printed (and therefore not copyrighted) until after his death.” His son sued the publisher after the work came up for renewal, claiming that this was not a posthumous work and thus he had the right to renew. The lower court sided with the publisher’s view that the work was posthumous, but the Appeals judge disagreed, reversing lower opinion. “Peter Bartok argues that the work is not posthumous”. This would give him right to renew as kin. Publisher Boosey & Hawkes, “the music publisher and proprietor of the initial copyright”, argues that the work was posthumous and thus that assignment they received from the composer entitled them to the renewal term. The work was composed between August 15 and October 8, 1943, and was first performed December 1 and 2, 1944, in Boston. Subsequent performances occurred and there was a radio broadcast during the composer’s lifetime. Composer “Bartok assigned his rights… to Boosey pursuant to their 1939 publishing contract.” Copyright was secured March 20, 1946, and that term expired March 1974. “Both Boosey and Peter Bartok filed renewal applications. The Register of Copyrights permitted the filing of both renewals expressly declining to adjudicate between them.” The Appeals Court said that the intent of Congress gets “controlling weight”. The Court determined that the Concerto was not to be viewed as a posthumous work because the contract was effected during author’s lifetime. Posthumous works are those where the widow and children are the ones who make the arrangements for publication. They are thus the “original proprietors” and “they would have no need of” the protections afforded by the rules for non-posthumous publication. “In this case, however, where the copyright contract was executed before the author’s death, the family has no means of protection other than the statutory renewal right…” Consequently, the publisher was in the same position with the heir(s) as had the author died after publication and after copyright registration but before eligibility for renewal. (The Appeals Court decision notes that the lower-court judge had relied on the definition of “posthumous” on the Register of Copyrights Form (Circular 1B), “yet the Copyright Office has no authority to give opinions or define legal terms and its interpretation on an issue never before decided should not be given controlling weight.”) (Not that these facts had any effect on the decision, but the decision reports that publication had been delayed owing to interruptions in mail service that were the result of London being extensively bombed during the last months of WWII.) John Marascalco, dba Robin Hood Music vs Fantasy Inc., dba Jondora/Parker MusicUSDC Central Div. Calif. (10-24-1990) ¤ CCH 26,651USCA 9th Cir. (12-30-1991) affirmed ¤ 953 F.2d 469, CCH 26,850; certiorari denied by U.S. Supreme Court (5-18-1992) 504 U.S. 931, 112 S. Ct. 1997, 118 L. Ed. 2d 592“In 1956, John Marascalco and Robert A. Blackwell co-wrote the song ‘Good Golly Miss Molly’… . On July 23, 1956, in exchange for royalties, Marascalco and Blackwell assigned their copyright interests in the song, including ‘any and all renewals of copyright’ to Venice [Music]. Venice registered the song with the Copyright Office on January 22, 1957, naming Venice as the copyright owner and Marascalco and Blackwell as the authors. On October 15, 1959, Blackwell assigned his royalties back to Venice. In 1973, Venice assigned its interest in the song to Argosy Ventures, which, in turn, assigned the interest to Fantasy, Inc. “On January 18, 1985, Marascalco renewed the song’s copyright in his name and Blackwell’s name. Two months later, Blackwell died. Blackwell’s death occurred during the twenty-eighth year of the song’s copyright. Blackwell’s daughters, Kelly Blackwell and Sandra Blackwell McClendon, inherited their father’s estate, including any interest he had in the song’s copyright. On March 15, 1986, Blackwell’s daughters assigned their interest in the song’s copyright to Marascalco in exchange for royalties. “Fantasy’s refusal to recognize Marascalco as the assignee of Blackwell’s interest prompted this action for a declaration of rights. Marascalco does not contest Fantasy’s ownership of the other one-half interest of the copyright. “The issues presented [include] whether Blackwell’s renewal interest in the song’s copyright was vested at the time of his death.” “The key question presented by this case is at what point does an author’s copyright renewal interest vest so as to invoke the rights of his successors… . “Marascalco and Blackwell’s original copyright term [would have] expired January 22, 1985, with the renewal period—the one year period prior to the copyright’s expiration during which time the copyright can be renewed—extending from January 22, 1984 to January 22, 1985. However, after the enactment of section 305 [effective 1978, and applicable to earlier works], the renewal period ran from December 31, 1984 through December 31, 1985. Thus, Blackwell died during the renewal period, but after Marascalco had timely effected a renewal registration in both authors’ names. “It is well settled that an author may assign his copyright’s renewal interest at any time during the copyright’s original term. However, until the renewal vests, the assignee has nothing more than a mere expectancy interest. The ‘assignees of renewal rights take the risk that the rights acquired may never vest in their assignors.’ Miller Music Corp. v. Charles N. Daniels, Inc. (1960) “Thus, the question becomes when does a copyright’s renewal interest vest… . Marascalco argues that the renewal interest does not vest until the beginning of the renewal term—in this case, January 1, 1986. Accordingly, since Blackwell was not alive at the commencement of the renewal term, the renewal rights passed to Blackwell’s daughters, under section 304(a), and then to Marascalco via assignment. Conversely, Fantasy argues that the renewal rights vested on the date Marascalco registered for renewal, January 18, 1985. Accordingly, since Blackwell was alive on that date, the renewal interest was vested in Fantasy… . “Since the congressional intent of the renewal term was to protect the rights of authors and their families, the Supreme Court in Miller Music Corp concluded that the author’s estate retains the renewal interest if an author assigns his interest but dies before the commencement of the copyright’s renewal period. However, the Miller Court did not reach the issue of when the renewal rights vested because the author died prior to the renewal period… . “Since Blackwell died before the commencement of the renewal term of the song’s copyright, Fantasy’s expectancy interest did not vest. Therefore, Blackwell’s renewal interest in the song’s copyright passed to his daughters, and they, in turn, effectively assigned their interest to Marascalco.”

The Copyright Registration and Renewal Information Chart and Web Site | ||||||||