13A similarity

About This Page

This page contains the following subsections:

13A.1 — similarity: subconsciously created (go there)

13A.2 — similarity: different markets (go there)

Where to Look in the Law

1909 Act: Implied in §§1, 2

1947 Act: Implied in §§1, 2

1976 Act: Implied in §§106, 107

What the Supreme Court Ruled

Sheldon vs Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corporation

309 U.S. 390 (3-25-1940)

The Supreme Court found that MGM in making its motion picture Letty Lynton (1932) “worked over old material,” specifically “a trial in Scotland, in 1857, of Madeleine Smith for the murder of her lover”. The 1930 play Dishonored Lady had been based on the same murder and trial. MGM had negotiated for the movie rights, decided that $30,000 was too high a price, then instead bought rights to Mrs. Belloc Lowndes’s 1930 novel Letty Lynton, also based on the story of Madeleine Smith. The Court determined: “But not content with the mere use of that basic plot, [MGM] resorted to petitioners’ copyrighted play. They were not innocent offenders. From comparison and analysis, the Court of Appeals concluded that they had ‘deliberately lifted the play’; their ‘borrowing was a deliberate plagiarism’.” The owners of the play wanted all of the $587,604.37 profit earned by the movie. “The District Court (26 F.Supp. 141) thought it ‘punitive and unjust’ to award all the net profits to petitioners. The court said that, if that were done, petitioners would receive the profits that the ‘motion picture stars’ had made for the picture ‘by their dramatic talent and the drawing power of their reputations’. ‘The directors who supervised the production of the picture and the experts who filmed it also contributed in piling up these tremendous net profits’. The court thought an allowance to petitioners of 25 per cent. of these profits ‘could be justly fixed as a limit beyond which complainants would be receiving profits in no way attributable to the use of their play in the production of the picture’.” The Court of Appeals agreed that fair “apportionment” was proper remedy but set it at 20%. The Supreme Court ruled, “The purpose is thus to provide just compensation for the wrong, not to impose a penalty by giving to the copyright proprietor profits which are not attributable to the infringement.” When determining what factors created profits, the Court recognized that star Joan Crawford was the draw for “the title of the picture is not identified with any well-known play or novel. Here, it appeared that the picture did not bear the title of the copyrighted play and that it was not presented or advertised as having any connection whatever with the play. It was also shown that the picture had been ‘sold’, that is, licensed to almost all the exhibitors as identified simply with the name of a popular motion picture actress before even the title Letty Lynton was used.” Expert witnesses called by MGM estimated the percentage of profits attributable to material in the play as from 5%-12%, with one saying the play contributed nothing, and with the other side giving no rebuttal. The owners of the play were thus given “the benefit of every doubt” in being awarded 20%. What the Lower Courts RuledStory vs HolcombeC.C.Ohio (Nov. term 1847) ¤ Fed.Cas.No.13,497Holcombe’s non-fiction book had been published without the knowledge of Story, yet portions of Holcombe’s book substantially resembled Story’s. Story’s 1842 pages was several times more than Holcombe’s 348, yet the Court determined that, adjusting to calculate on the basis of pages the same size, Holcombe had a ratio of copying from Story (as against material Holcombe had not so copied) of 2:9. This was judged an infringement. The first 100 pages of Holcombe were deemed a clear infringement, yet even the rest of Holcombe has the same plan as Story, despite different wording. Frank Shepard Co. vs Zachary P. Taylor Pub. Co.C.C.A.N.Y. (3-20-1912) ¤ 193 F. 991, 113 C.C.A. 609.The Shepard and Taylor companies both published citations of court decisions. A copyrighted book contained errors. Subsequent editions reproduced them. A book from the rival contained 138 of these same errors. (13 were citations to court cases which never existed.) The court considered this proof of copying. “We think that the proof of a considerable number of errors common to both publications occurring first in the complainant’s and none occurring first in the defendant’s [publication] created a prima facie case of copying by the defendant which it was bound to explain. “The burden of proof … [normally] was on the complainant …, but on this … the burden of evidence… was on the defendant.” Chicago Record-Herald Co. vs Tribune AssociationC.C.A., Ill. (4-26-1921) ¤ 275 F. 797The Herald newspaper versions of the same story which appeared in the Tribune “present the essential facts of that article in the very garb wherein the author clothed them, together with some of deductions and comments in his precise words, and all with the same evident purpose of attractively and effectively serving them up to the reading public. Whether the appropriated publication constitutes a substantial portion of that which is copyrighted can not be determined alone by lines or inches which measure the respective articles. We regard the Herald publication as in truth a very substantial portion of the copyrighted article, and the transgression is its unauthorized appropriation is not to be neutralized on the plea that ‘it is such a little one.’” Marks vs Leo Feist, Inc.C.C.A.N.Y. (4-2-1923) ¤ 290 F. 959Marks copyrighted “Wedding Dance Waltz” December 28, 1905, Feist had his song “Swanee River Moon” copyrighted April 4, 1921. The composer of the 1921 song swore he never knew of the 1905 waltz. Within the 450 bars of the waltz was contained six bars similar to those found in the chorus of the later work. The Court remarked that given the limited possible combinations of notes, it was possible for there to be unintentional copying, yet here the “rhythm and accent are entirely different.” Furthermore, even earlier than Marks’s 1905 work there was “Cora Waltz” which has four bars duplicated in “Wedding Dance Waltz.” Feist was exonerated. Simonton vs Gordon et al.D.C.N.Y.(2-17-1925) ¤ 12 F.2d 116Ira Vera Simonton, author of a novel entitled Hell’s Playground, sued over a play by Leon Gordon entitled White Cargo, citing similar incidents. The judge enumerates many, even as he recognized differences. He said a mix of similarities and differences is usually true of plays adapted from novels, “and I have but little doubt that, if the play were represented as being a dramatization of ‘Hell’s Playground’, it would be so accepted.” Roe-Lawton vs Hal E. Roach StudiosD.C.Cal. (3-7-1927) ¤ 18 F.2d 126

Roe-Lawton had copyrights in five magazine stories from 1915 to 1918, and claimed that two movies produced by Roach and released in 1924 and 1925 infringed his stories. These were stories “in which the dramatic interest was centered upon a wild horse, and in which the underlying motive”, as in the magazine stories, was of “the power of the human to subdue and win the affection of the animal.” The Judge decided, “It is intimated in some decisions that the appropriation of a theme violates an author’s copyright. In its ordinary meaning, a theme is understood to be the underlying thought which impresses the reader of a literary production, or the text of a discourse. Using the word ‘theme’ in such a sense will draw within the circle of its meaning age-long plots, the property of every one, and not possible of legal appropriation by an individual.” Was there appropriation? The Judge wrote that real-life equivalents of such wild horses are “well known”. Further: “That the horse, however, wild and untamed, can be overcome by man and reduced to a state of subjugation, is a matter also of common knowledge… . As familiarly known, also, is the fact that such an animal may acquire great affection for the man who conquers it.” Here the stories are different other than for “natural and expected happenings, considering the normal action of animals placed as the characters are in the environment in which we find them.” (The titles of the movies are not given; however, an expert on the films produced by Hal Roach answered the CopyrightData.com editor that Roach during this period did not produce any films centered on horses other than those starring Rex the Wonder Horse. The first two made were The King of Wild Horses (1924) and Black Cyclone (1925). A third film, Devil Horse, was reviewed by Variety June 9, 1926, but not released until September 12 (according to AFI), so it may have escaped the notice of the plaintiff as this suit was prepared for court.) (The expert who extended the courtesy mentioned above is Richard M. Roberts, author of Past Humor, Present Laughter: Musings on the Comedy Film Industry 1910-1945, volume one: Hal Roach, a book not yet published as of when this web page was updated.) Anne Nichols vs Universal Pictures Corporation, Carl Laemmle and Harry PollardDC SDNY (5-14-1929) ¤ 34 F.2d 145; affirmed 45 F.2d 119; cert denied by S.Ct.

Witwer vs Harold Lloyd Corporation, et al [including Pathe Exchange]D.C.Cal. (11-18-1930) ¤ 46 F.2d 792.Harold Lloyd Corp. et al vs WitwerC.C.A., 9th Cir. (4-10-1933) ¤ 65 F.2d 1, certiorari dismissed 54 S.Ct. 94, 78 L.Ed. 1507

Benjamin Ansehl vs Puritan Pharmaceutical Co.C.C.A.Mo. (9-7-1932) ¤ 61 F.2d 131, certiorari denied 53 S.Ct. 224, 287 U.S. 665, 77 L.Ed. 374Altering a copyrighted work by paraphrasing and substitution of similar illustrations, is still near enough to exact plagiarism to be infringement. “The fact that the identical language or the identical illustrations were not used will not justify the appropriation of copyrighted articles.” M.P. Echevarria vs Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc., and othersS.D.Cal. (10-30-1945) ¤ 12 F.Supp. 632, 28 USPQ 213“In Echevarria v. Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc., a Filipino writer had composed a scenario to which he gave a Latin name: ‘Nulias Filias.’ He published it in a magazine known as the ‘Scenario Bulletin Review,’ and he claimed that it was plagiarized in a Warner Bros.’ play called Across the Pacific. I pointed to the fact that any play which dealt with the Philippines at the time of the American occupation had, perforce, to bring in Aguinaldo, the Filipino leader, and General Funston; that they are historical figures so connected with the event that it would be impossible to write a story of the Spanish-American war and its sequel without having the two protagonists in it. The writer claimed that this was the greatest similarity between the two. The answer was: ‘If originality can be claimed in opposing Aguinaldo to Funston, as the plaintiff claimed in open court, then all the novels, short stories, and dramas written about the Civil War, opposing Grant and Lee, might never have been written after the first one, because the author of the first one could have claimed exclusive right to the idea.’ “And the conclusion expressed that, aside from this similarity, which placed the two national heroes in conflict, there was no other similarity between the two works. There, too, access was assumed. “In sum, the first fundamental to be deduced from these cases is, that once we deal with a particular situation which is not original with any one, it calls for certain sequences in the methods of treatment, which cannot be avoided, because they are, in the very nature of the development of the theme, and are used by every writer who knows his craft.” (Quoted from the decision of Schwarz v. Universal Pictures Co., D.C.Cal.(1945), 85 F. Supp. 270, which had been decided by the same Judge Yankwich as Echevarria.) Mort Eisman, Clara Dellar and Robert Louis Shayon vs Samuel Goldwyn, Inc., Samuel Goldwyn, United Artists and Eddie CantorDC SDNY (5-24-1938)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The decision was reversed because a cutting continuity had been used as evidence in place of the actual movie. The appellant had argued about differences between the continuity and the movie. The Court said the movie would be viewed. |

Bein vs Warner Bros. Pictures

C.C.A.N.Y. (7-20-1939) ¤ 105 F.2d 969, 42 USPQ 395

Albert Bein wrote the novel Youth in Hell and (using the same content) the play Road Out of Hell. The play was revised as Little Old Boy. All three were said to be infringed by Warner Bros.’s movie Mayor of Hell (1933). In 1931, a successful producer of plays (named Harris) had been interested in producing Bein’s play , and assigned “one Chodorov” to work with Bein on rewrites. No play was produced, and after the option lapsed, Chodorov went to work for Warner Bros. and wrote the allegedly-infringing screenplay. The Court said that in comparing the novel and the plays to the movie, there is “similarity in a few incidents and a few points of dialogue”. What is most striking is that all of the works concern young troublemakers confined to reform school.

Bein claimed in Court that prior to Chodorov leaving New York to write in Hollywood, Bein “orally imparted to Chodorov an uncopyrighted play, utterly different from his copyrighted plays but quite close to the defendant’s motion picture. The district judge held that the plaintiff’s testimony as to this uncopyrighted play was untrue, and on appeal the plaintiff makes no claim to the alleged uncopyrighted play.” What’s more, Chodonov testified that the story of the movie was based on one by “one Auster” purchased by Warner Bros. “There is a close similarity between the Chodorov screen play and the story by Auster.”

(EDITOR’S NOTE: That Warner Bros. could establish that they had bought the Auster property was a boon for them, because the story of Mayor of Hell had by the end of 1939 been remade twice: as Crime School (1938) and Hell’s Kitchen (1939), both featuring the “Dead End” Kids. Each of the two later movies gets some of its plot material from Mayor of Hell yet has plot points not from the 1933 movie. Between the 1938 and 1939 films, almost all of the plot points from Mayor of Hell are reused.)

Michael I. Kustoff vs Charles Chaplin and others

D.C.Cal. (1-23-1940) ¤ 32 F.Supp. 772, affirmed 120 F. 2d 551

Kustoff vs Chaplin, et al

CCA, 9th Cir. (5-24-1941) ¤ 120 F.2d 551, 49 USPQ 580

| |

Kustoff wrote “Against Gray Walls or Lawyer’s Dramatic Escapes” prior to April 16, 1934. A copyright of 1934 is on the title page; registration occurred July 2, 1934. Kustoff delivered a copy to Michael Shantzek, who represented that he had access to Charlie Chaplin (though he was never Chaplin’s agent), but no evidence was given in court that Shantzek ever delivered the book to Chaplin or to any Chaplin employee, writer or agent. Chaplin testified that he had not read it, nor had Carter DeHaven, the only person with whom Chaplin collaborated on Modern Times (Chaplin’s 1936 movie). Kustoff contended that the movie infringed on his book. The District Court viewed Modern Times, but decided “Such matters indicating access to the said book are not a substantial copying.”

Kustoff, having not gotten the verdict he wanted the first time around, filed for appeal. The decision of the Appeals Court reported additional evidence in favor of Chaplin.

“Chaplin’s testimony was that he had had in mind the general idea of the photoplay many years before production of the film was begun; and there was further testimony that the writing of synopses of incidents, scenes and sequences… was commenced early in 1933. The picture was released for exhibition to the public in 1936.” Thus, the fact of the book being copyrighted and published in 1934 meant that these occurred after Chaplin had taken crucial actions but before these had become apparent to the public.

Just as the previous court was not given evidence to substantiate that Chaplin was shown the book at a time when this would have influenced his movie, this court found no such evidence either. Further, this court remarked that had there been evidence that “appellee did read the book before or in the course of production of the motion picture, this, of itself, avails appellant nothing. Reading, alone, is not sufficient to show infringement.”

Solomon vs R.K.O. Radio Pictures

D.C.N.Y. (4-14-1942) ¤ 44 F.Supp. 780, 53 USPQ 468

The RKO movie Radio City Revels (1938) was said to have infringe an unproduced play called “It Goes Through Here.” “In both works, the basic idea or theme is centered around a character who is possessed of a subconscious creative ability. Such idea, which is a mere subsection of a plot, irrespective of whether it is original or not, is incapable of protection, since ideas as such are not protected by Copyright Law.” In answering the question of whether the net impression of the movie was that it copied the play, the decision quotes the earlier Dymov v. Bolton case: “‘It requires dissection rather than observation to discern any resemblance here.’”

Stonesifer vs Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation

D.C.S.D.Cal. (12-30-1942) ¤ 48 F.Supp. 196, 56 USPQ 94

Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation vs Stonesifer

C.C.A.Cal. (2-10-1944) ¤ 140 F.2d 579, 60 USPQ 392

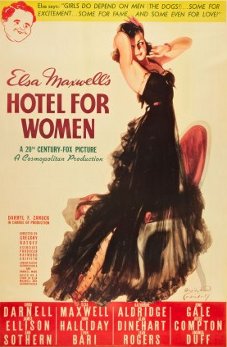

Myrtle Louise Stonesifer (aka Louise Howard) contended her play “Women’s Hotel” was infringed by Twentieth Century-Fox’s movie Hotel For Women. She based her characters on people she knew at Allerton House, a woman’s hotel in New York City. She produced the play at the Villa Venice in New York City, which she operated. It was performed just once (July 1937). Frank Underwood, associate story editor at TCF, attended and requested that Stonesifer submit the play to him, which she did. The copy was returned several weeks later. In August 1939, TCF exhibited Hotel For Women. Darryl F. Zanuck

|

|

The District Court decided that an “ordinary observer who had read or seen the plaintiff’s play would recognize the infringement in the film”. Damages awarded to Stonesifer were based on the net profits of the film. Testimony had established: Negative cost $510,300; Positive prints $134,200; Distribution $197,900 (these last three were the costs); Total film rentals $862,200; net profit $19,800. Damages assessed by court were $3,960 together with costs ($1000 for reasonable attorneys fees).

The Appeals Court took into account that although “there can be no infringement of copyright without some copying, the mere fact of similarity between two works does not of itself make one an infringement of the other.” The decision notes “the absence of direct evidence of copying”. Nonetheless, this decision (as had the District Court decision) spends pages recounting similarities. Example: “In both appellee’s dramatic composition and in appellant’s motion picture the principal characters, Margaret and Marcia, are unsophisticated young ladies who go to New York City and register at a hotel for women. Margaret came from a small town in Illinois; Marcia came from Syracuse, New York. Each becomes involved with older men who attempt to take advantage of their inexperience. In both the climax is reached in the respective apartments of these men when a jealous woman, who had a short time previously called by telephone and was deceived, enters the apartment and fires a pistol.”

Where there are dissimilarities, the Appeals Court found them more incidental than substantive: “It is true, as appellant argues, that the film and appellee’s composition differ in numerous respects. Such dissimilarities result, however, principally from the film’s enlarged means to express in a wider latitude incidents necessarily requiring a wider range of settings than a play restricted to the narrow confines of a theatrical stage is able to present.”

The Appeals Court retained the lower court method of determining the award: “It is now settled that where a portion of the profits of an infringing work is attributable to the appropriated work, to avoid an unjust course by giving the originator all profits where the infringer’s labor and artistry have also to an extent contributed to the ultimate result, there may be a reasonable approximation and apportionment by the court of the profits derived therefrom.”

Dorothy West and Madge Christie vs Eric Hatch and others [including Universal Pictures, MacFallen Publications and Grosset & Dunlap, Inc.]

D.C.N.Y. (2-9-1943) ¤ 49 F.Supp. 307

The play This Modern Instance (produced in Delaware) and the story “My Man, Godfrey” (the basis of a 1936 movie of the same title) each had a butler of a wealthy family, plus maids, cooks and detectives. Each is set during the Great Depression and dramatize loss of fortunes. However, the butler differs in importance between the works (“second fiddle” in the first, lead character in the second) and the families differ in structure, so the at-first-look similarities don’t add up to plagiarism. “Maids and cooks, also, are part and parcel of almost every household comedy.” “My Man Godfrey” had first been published in Liberty magazine, then by Grosset & Dunlap, then had been made into a Universal movie. |

||||

Gingg vs Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation

D.C.,S.D.Cal. (6-12-1944) ¤ 56 F. Supp. 701

Plaintiff owned the song “There’ll Never Be Another You” (1941), which he believed had been infringed by Twentieth Century-Fox’s song “There Will Never Be Another You” (1941). The defendant could point to its copyright in the earlier similar song “Never in a Million Years” (1936).

The Court found that similarity of two works may be taken as evidence of copying but not as proof of copying. There must have been copying for there to have been infringement.

Remick Music Corp., et al. vs Interstate Hotel Co. of Nebraska;

Kern, et al. vs Interstate Hotel Co. of Nebraska

D.C.,D.Neb.,Omaha Div. (12-9-1944) ¤ 58 F.Supp. 523, affirmed 157 F.2d 744, certiorari denied 67 S.Ct. 622, 329 U.S. 809, 91 L.Ed. 691, rehearing denied 67 S.Ct. 769, 330 U.S. 854, 91 L.Ed. 1296.

C. Arthur Fifer copyrighted his song “Lola” as “a music composition, not reproduced in copies for sale,” on April 22, 1940, depositing one copy in the copyright office. On February 4, 1941, he copyrighted the song again, now as a fox trot, this time depositing “two copies of an orchestral arrangment… made by Ken Macomber, the arrangement being said in the certificate to have been published January 23, 1941. Fifer’s song had its third and last registration as a published work, filed by Broadcast Music Inc., “with May 12, 1941 as the date of publication and May 26, 1941 as the date of deposit of the required two copies.”

Meanwhile, removed from Fifer, successful lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II wrote the words to “The Last Time I Saw Paris,” which he dictated to his partner who wrote the music. “Mr. Jerome Kern, the composer [produced in court] by photographic copy, the original music manuscript on which he had written by dictation from their author the words of the lyric and the preliminary musical notes themselves, some time in the summer, and probably in June of 1940.”

The problem? The two works are alike. As the court decision declares: “That there is a striking melodic similarity between the dominant musical theme of the Macomber arrangement of the chorus of ‘Lola’ (which is only about half as long as that of ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’) and certain portions of the chorus of ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’ is unquestionable. Yet, even these similar portions of the two compositions are not identical, as the musical witness for the defendant acknowledged, while stating that ‘I think the average listener on the first hearing would think the tunes were nearly identical.’ Even there, they are differently notated; and ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’ both contains certain striking melodic differentiations from ‘Lola,’ notably a mildly shocking dissonance in simulation of Parisian taxicabs’ ‘squeaky horns’, by way of ‘suiting the action of the word,’ which in its creation preceded the music, and also is much longer and varied in its chorus, to say nothing of its introductory verse, with which no evidentiary comparison was made on the trial.”

So what was the verdict? Kern was exonerated of infringement of “the musical or verbal content of C. Arthur Fifer’s initial filing of an unpublished composition in the copyright office on April 22, 1940” (the only version which “could possibly have antedated both the composition and final copyrighting of ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’”), owing to “a complete want of evidence either of access, or of the possibility of access, by Mr. Kern to information touching ‘Lola.’ Access either in fact or in probability is simply not shown. And the improbability of such access is inferable from standing instructions of the Register of Copyrights forbidding it in cases of unpublished filings”.

The Court found “the existence of novelty and originality in the music of ‘The Last Time I Saw Paris’”. Also working against the owners of “Lola” was that of the three versions copyrighted, only the Macomber arrangement was offered at trial, and even here, “no complete copy, but only a single sheet of four pages, evidently for a piano as one orchestral instrument, and… probably… in specially arranged form, the chorus only of ‘Lola’”. Who knows why this withholding?

(Copyright Office documentation on both songs is reproduced on the chart pages of this web site: the renewal page for “Last Time” and copyright status investigation page for “Lola.”)

(Jerome Kern had by the time of this case written numerous popular song over the course of three decades. About two dozen of these (including “The Last Time I Saw Paris”) were incorporated into MGM’s movie Till the Clouds Roll By (1946), a fanciful biography of Kern which is widely-available on bargain DVDs owing to non-renewal of the copyright. Oscar Hammerstein II co-wrote with Kern the Broadway smash Show Boat (1927), before starting in 1943 a collaboration with Richard Rodgers that created many of theater’s best-loved musicals. “The Last Time I Saw Paris” won the Academy Award for Best Song of 1940.)

illustration: part of the sheet music of “Lola,” showing a section of the chorus. This is reproduced from the May 1941 published version. The song entered the public domain for lack of copyright renewal in 1969.

EDITOR’S ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: I do not read music, so I am indebted to Brent Walker of the band Del Noah and the Mt. Ararat Finks for recording a performance of “Lola” for me from the sheet music I provided him. — David Hayes

Jack Schwarz vs Universal Pictures Co., Inc, et al

USDC SDCal C.D. (12-19-1945) ¤ 85 F.Supp.270, 83 USPQ 153

A manuscript titled “Ambitious Lady” had been submitted by a motion picture agent and returned to the author on April 15, 1941. When Universal released the movie His Butler’s Sister in 1943, Schwarz assumed it was an infringement. However, the work of the plaintiff submitted on March 21, 1941, was “an embryonic scenario of only a page and a half, entitled ‘His Butler’s Sister’”. That same day, popular Hollywood columnist Louella Parsons in her newspaper column mentioned this title as forthcoming. The studio had already been working on the basic idea for some time, for the Court reports, “We have at least five scenarios antedating March 27, 1941.” The decision indicates that the plaintiff and studio each wrote of “master, butler, and butler’s sister, and of the master’s ball” — which anyone could appropriate.

“[T]he only similarity which exists is in the theme — if we make an abstraction of the theme, and call it a ‘desire to achieve’. In one case it is literary fame; in the other, musical fame; in each case through a certain, particular person. But there the similarity ends. And from there on the means used in the development of the characters introduced, the personalities involved, the manner of reaching the climax, the manner of achieving the triumph of the girl, are so different that I cannot see how anyone who reads the story and sees the picture, without prejudgment, can say that there is anything of importance in one which is carried over into the other.”

Universal Pictures Co. vs Harold Lloyd Corp.

C.C.A.Cal. (5-12-1947) ¤ 162 F.2d 354, 73 USPQ 317

“The motion picture Movie Crazy was a world wide success when first shown [1932], and it realized $400,000 profits at the time of a world depression. These facts are proper items for consideration of value.” The popular star of the movie, Harold Lloyd, produced it and had long worked with at least one of its writers, Clyde Bruckman, who was paid $42,900 as writer and credited director of that film. Movie Crazy had cost $650,000 to make. One of its highlights was the “magician’s coast sequence,” which had “cost approximately $188,000.”

In 1943, Universal Pictures employed Bruckman as writer for a modest comedy called So’s Your Uncle, on which Bruckman wrote in a repeat of the “magician’s coat sequence.” “The sequence in question consisted of 57 consecutive comedy scenes or 20% of the entire feature.” (EDITOR’S NOTE: The “comedy scenes” might better be described as comedy incidents, gags, and what the decision calls elsewhere “stage business” and “comedy accretion”.) The “last 300 feet of reel 7 and the first 700 of reel 8 of Movie Crazy … are reproduced in … the first 600 feet of the 4th reel of So’s Your Uncle.” (EDITOR’S NOTE: Those who have not seen either film might know the scene from a Three Stooges comedy called Loco Boy Makes Good (1942), which was yet another occurrence of Bruckman earning a paycheck by re-submitting the scene. A short subject, the Stooges film does not seem to have become the object of any legal action which led to a trial.)

The District Court awarded Lloyd $4,000, which was 20% of the $20,000 profit earned by So’s Your Uncle. Lloyd appealed on the grounds that this was not enough to compensate for his loss. There was validity to this argument.

“There was substantial evidence showing that the infringed picture was valuable theatrical property and that the past profits and the cost of production were proper elements to consider in determining damages. The picture was exhibited in 6636 theaters throughout the United States. Several expert witnesses testified as to the values inherent in the picture, including the re-issue and re-make rights, assertedly destroyed by exhibition of the infringing picture.”

“We are of the opinion that there is substantial evidence in the case to show that property rights and present existing intrinsic property values have been impaired or destroyed. The testimony of the expert witnesses clearly establishes that the picture’s value has been lessened by the appropriation of an important sequence by the appellants and it is common knowledge that the repeated use of comedy, detracts from its force as amusement.” Nonetheless, the Appeals Court adopted the precedent of the Sheldon and Stonesifer cases that apportionment of profits “avoids an unjust course”. (All quotes are from Appeals Court decision.)

Edward Dunbar O’Brien vs Chappel & Co. and John Larson, et al

USDC SDNY (2-10-1958) ¤ 159 F.Supp. 58

The court decision states that the complaint “is a hodgepodge of unrelated and vague accusations and allegations”, among them:

1) O’Brien’s unpublished composition “Paddle Wheel,” which contains the lyric “When you’ll be mine, night and noon,” was read by Larson, and that (allegedly) Larson, in conjunction with Alan Jay Lerner while the latter was writing My Fair Lady, plagiarized this when Lerner wrote, “I’ve grown accustomed to the tune you whistle night and noon.”

2) O’Brien discussed with Larson “a literary production called ‘Call Me Mom’ which was a monochrome production done in black and white,” and that this was copied in My Fair Lady during its “Ascot Scene” “where the actors and actresses appear in black and white.”

“The plaintiff apparently thinks he can get sole rights to the use of the phrase ‘night and noon’ no matter in what context it is used. Such a common phrase in and of itself is not susceptible of copyright nor of appropriation by any individual. Likewise plaintiff cannot get copyright or literary rights, to the idea of having the actors and actresses in a stage show appear in a scene in black and white costumes.” Case dismissed.

Irving Berlin vs E.C. Publications, Inc.

USDC SDNY (6-27-1963) ¤ 219 F.Supp. 911, 138 USPQ 298

Irving Berlin vs E.C. Publications, Inc.

Court of Appeals, 2nd Cir (3-23-1964) ¤ 329 F.2d 541

Mad magazine published song parodies which could be sung to tunes written by Irving Berlin and other top songwriters. The magazine did not reproduce the music notes nor supply recordings, but merely published the new lyrics created by the magazine along with a notation as to what well-known song the lyrics could be sung to. Berlin sued. The Court concluded: “It is obvious that defendants’ lyrics have little in common with plaintiffs’ but meter and a few words, except in two instances which will be discussed below. Defendants have created original, ingenious lyrics on subjects completely dissimilar from those of plaintiffs’ songs.” (The “two instances” are immaterial to the conclusion about little commonality and thus are outside the scope of this web site.)

Land vs Jerry Lewis Productions, Inc., et al

Calif. Sup. Crt, L.A.Co. (1-20-1964) ¤ 140 USPQ 351

Suit was filed against movie comedian/director/producer Jerry Lewis alleging that Lewis’s successful feature-length comedy The Nutty Professor (1963) plagiarized the plaintiff’s script. The judge ruled that other than both scripts being variations on Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, the works were as dissimilar as War and Peace is to Gone With the Wind.

Clyde Ware vs Columbia Broadcasting System, et al

Calif. Court of Appeals, 2nd Dist, Div. 4 (8-11-1967) ¤ 61 Cal.Rptr. 590, 253 A.C.A. 832

An episode of television’s Twilight Zone titled “Miniature” (which stars Robert Duvall) was considered to be an infringement of a play called The Thirteenth Mannequin by the author of that play. The Twilight Zone episode was withheld from syndication because this case had not yet gone to trial. (After CBS won in court, the episode remained out of circulation because the syndication package had already been assembled. “Miniature” would not be broadcast again until 1984.) The Court found only flimsy resemblances between the works. “[T]he theme or idea of a man who finds happiness with an inanimate figure, whom he treats as a real person,… is at least as old as Ovid’s myth of Pygmalion and Galatea,… [and thus] could not be the private property or monopoly of any author.” | ||||

Warner Bros., Inc., Film Export, A.G., and DC Comics, Inc. vs American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., and Stephen J. Cannell Productions

USDC,SDNY (9-24-1982) ¤ 222 USPQ 544

USCA 2d Cir. (10-6-1983) ¤ 720 F.2d 231, 222 USPQ 101

The owners of copyright to the movies, TV shows and comic books of Superman sued over the similarities they saw in the ABC television series The Greatest American Hero. The Appeals Court recognized that there was similarity, particularly similar lines, yet, “In each instance the lines are used, not to create a similarity with the Superman works, but to highlight the differences, often to a humorous effect.” Example: “Look!… Up in the sky!… It’s a bird!… It’s a plane!… It’s… Crazy Eddie!” The Court contended that some phrases in Superman had become part of the culture’s vocabulary, and as such could not be denied use. (Compare the quoted dialogue: Listen to a sound clip in MP3 format (15K) from the title sequence of the 17 Superman cartoons of the 1940s. The same clip may be played from the bottom of this summary.)

The ABC series had avoided this potential trap: “A story has a linear dimension: it begins, continues, and ends. If a defendant copies substantial portions of a plaintiff’s sequence of events, he does not escape infringement by adding original episodes somewhere along the line.” (All quotes from Appeals case. The above one was later quoted in Murray Hill Publications, Inc., v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, USCA, 6th Cir (3-19-2004), 361 F.3d 312; 70 U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA) 1220; CCH 28,777)

The first court reported that Warner Bros. had received a copy of the pilot episode of The Greatest American Hero months prior to broadcast. They had not been left to be surprised by the content while there was time to adjust the content of the program.

Apple Computer vs Microsoft Corp.

9th Cir. (9-19-1994) ¤ 35 F.3d 1435

“Apple filed suit alleging that elements of Microsoft’s graphical user interface infringed on the copyright of Apple’s equivalent software. Significantly, Microsoft had obtained a license from Apple for some, but not all, elements of Apple’s software. The court stated that ‘where, as here, the accused works include both licensed and unlicensed features, infringement will depend on whether the unlicensed features are entitled to protection… . Because only those elements of a work that are protectible and used without the author’s permission can be compared when it comes to the ultimate question of illicit copying, we use analytic dissection to determine the scope of copyright protection before works are considered “as a whole.”’ In so concluding, the Apple court extended the application of filtering, from unprotectible elements to protectible elements used with the permission of the copyright owner.” (Quoted in Murray Hill Publications, Inc., v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, USCA, 6th Cir (3-19-2004), 361 F.3d 312; 70 U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA) 1220; CCH 28,777)

(The concept of “filtering” has been developed to judge cases of infringement of computer software. The details are outside the scope of this web site.)

Lebbeus Woods vs Universal City Studios, Inc. Atlas Entertainment, Inc., Terry Gilliam and Jeffrey Beecroft

USDC SDNY (3-29-1996) ¤ No. 96 Civ. 1516 (MGC), 920 F.Supp. 62

Universal’s movie 12 Monkeys reproduced Woods’s copyrighted drawing, so he sued to “enjoin Universal from distributing, exhibiting, performing or copying those portions… which reproduce his copyrighted drawing, or any portion of it. For the reasons that follow, Woods’ motion is granted.

“In 1987, Woods created with graphite pencil a detail drawing entitled ‘Neomechanical Tower (Upper) Chamber,’ which depicted a chamber with a high ceiling, a chair mounted on a wall and a sphere suspended in front of the chair.” (The description continues for several lines.) This version was published in Germany in 1987 and after Woods colored his black and white drawing in 1991, that “version was included in a collection of Woods’s illustrations entitled Lebbeus Woods/The New City, published in the United States in 1992.

“In late December 1995, Universal released 12 Monkeys. At the start of the movie, the main character is brought into a room where he is told to sit in a chair which is attached to a vertical rail on a wall. The chair slides up to a horizontal ledge on the wall so that the chair is several yards above the ground. A sphere supported by a metal-frame armature descending from above is suspended directly in front of the main character.” (All these details resembles those in the full description merely excerpted above.)

Woods saw the movie on January 18, 1996, having been apprized of the similarity. Woods’s copyright had been taken out on the collection The New City, which Universal argued was a compilation and thus its copyright “only covers the selection and arrangement of Woods’ illustrations, not the earlier published illustrations themselves.” Yet, because (as applies here) “the owner of the copyright for a collective work also owns the copyrights for its constituent parts, registration of the collective work satisfies the requirements of Section 411(a) for purposes of bringing an action for infringement for any of the constituent parts… .

“Universal cannot seriously contend that ‘(Upper) Chamber’ was not copied during the filming of 12 Monkeys. Terry Gilliam, the director, admits that in preparing the design of 12 Monkeys, he reviewed a copy of a book that included ‘(Upper) Chamber.’ Gilliam and Charles Roven, the producer, discussed the drawing with Jeffrey Beecroft, the production designer.

“A comparison of ‘(Upper) Chamber’ and footage from 12 Monkeys demonstrates that the movie has copied Woods’ drawing in striking detail.” The judge listed several instances of similarities, examples being that the walls have “the same worn texture”, chairs having patterns “comprised of four rectangular planes,” “the same pattern of horizontal and vertical etching on the upper part of the chair back.”

“Universal argues that the infringement is de minimis because the infringing footage in 12 Monkeys amounts to less than five minutes in a movie 130 minutes long. Whether an infringement is de minimis is determined by the amount taken without authorization from the infringed work, and not by the characteristics of the infringing work. As discussed here, 12 Monkeys copies substantial portions of Woods’ drawing.”

Although “Universal argues that 12 Monkeys had been in release for twenty-nine days by the time that Wood made his claim,” this was not an “unreasonably delay” that should excuse Universal, for “[t]here is no evidence that Woods knew or should have known of the infringement until early January 1996.” An injunction would mean withdrawal of the movie, to which Universal objected it would “suffer considerable financial loss”. The Court answered: “Copyright infringement can be expensive. The Copyright Law does not condone a practice of ‘infringe now, pay later.’ Copyright notification and registration put potential infringers on notice that they must seek permission to copy a copyrighted work or risk the consequences.”

The movie remained as it was. “The studio hastily settled with Woods for an undisclosed sum.” (Los Angeles Times, December 10, 1997) The film was not re-cut or re-shot. The closing credits were revised to include Woods’s name.

SunTrust (as trustee for the Stephen Mitchell trusts for the benefit of Eugene Muse Mitchell and Joseph Reynolds Mitchell) vs Houghton Mifflin

USDC N.D.Ga. (4-18-2001) ¤ 136 F. Supp. 2d 1357

USCA 11th Cir. (5-25-2001) ¤ 252 F.3d 1165 vacated preceding

USCA 11th Cir. (10-10-2001) ¤ 268 F.3d 1257

Alice Randall admits that her novel The Wind Done Gone (published June 2001) retells Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind (1936, yet a continuing top-seller). Having written her book without authorization from Mitchell’s heirs, she faced an infringement suit. The first court to hear the case (starting April 18, 2001) issued an injunction against publication owing to infringement, but the Appeals Court reversed (allowing publication yet finding grounds that damages should be awarded to Mitchell’s heirs). (The ban on publication was lifted May 25.) The Appeals Court remanded the case for new trial, then the parties settled out of court. Although this outcome deprives the public of the knowledge of how the next court(s) would have resolved the case, the different opinions reached by the two courts, and the application of the parody and fair-use principles by the Appeals Court, are illustrative. The out-of-court settlement followed the parameters of the Appeals Court findings. In the end, The Wind Done Gone was allowed to be published when Alice “Randall’s publisher, Houghton Mifflin, agreed to make an unspecified contribution to Morehouse College, a historically black school in Atlanta. In return, lawyers for [Margaret] Mitchell’s estate agreed to stop trying to block sales of Randall’s book, which tells the GWTW story from a slave’s point of view.” (The Associated Press, May 10, 2002) Morehouse College already was a beneficiary of the Mitchell Estate’s charitable contributions, so the infringing publisher’s donation to that institution amounted to a contribution to a charity already in line for any philanthropy in which the Mitchell Estate eventually engaged.

The Appeals Court wrote that “Alice Randall, the author of TWDG [The Wind Done Gone], persuasively claims that her novel is a critique of GWTW’s [Gone With the Wind’s] depiction of slavery and the Civil-War era American South. To this end, she appropriated the characters, plot and major scenes from GWTW into the first half of TWDG. According to SunTrust [acting on behalf of the Mitchell heirs], TWDG ‘(1) explicitly refers to [GWTW] in its foreword; (2) copies core characters, character traits, and relationships from [GWTW]; (3) copies and summarizes famous scenes and other elements of the plot from [GWTW]; and (4) copies verbatim dialogues and descriptions from [GWTW].’ Defendant-Appellant Houghton Mifflin, the publisher of TWDG, does not contest the first three allegations, but nonetheless argues that there is no substantial similarity between the two works or, in the alternative, that the doctrine of fair use protects TWDG because it is primarily a parody of GWTW… .

“In our analysis, we must evaluate the merits of SunTrust’s copyright infringement claim, including Houghton Mifflin’s affirmative defense of fair use. As we assess the fair-use defense, we examine to what extent a critic may use a work to communicate her criticism of the work without infringing the copyright in that work… .

“The case before us calls for an analysis of whether a preliminary injunction was properly granted against an alleged infringer who, relying largely on the doctrine of fair use, made use of another’s copyright for comment and criticism. As discussed herein, copyright does not immunize a work from comment and criticism. Therefore, the narrower question in this case is to what extent a critic may use the protected elements of an original work of authorship to communicate her criticism without infringing the copyright in that work.”

The Court found indisputable “(1) that SunTrust owns a valid copyright in GWTW and (2) that Randall copied original elements of GWTW in TWDG.” The Court went on to say that: “In order to prove copying, SunTrust was required to show a ‘substantial similarity’ between the two works such that ‘an average lay observer would recognize the alleged copy as having been appropriated from the copyrighted work.’” (Inner quotes from Original Appalachian Artworks, Inc. v. Toy Loft, Inc., 684 F.2d 821, 829 (11th Cir. 1982))

“There is no bright line that separates the protectable expression from the nonprotectable idea in a work of fiction.” Nonetheless, “After conducting a thorough comparison of the two works, the district court found that TWDG copied far more than unprotected scenes a faire from GWTW: ‘[TWDG] uses fifteen fictional characters from [GWTW], incorporating their physical attributes, mannerisms, and the distinct features that Ms. Mitchell used to describe them, as well as their complex relationships with each other. Moreover, the various [fictional] locales, … settings, characters, themes, and plot of [TWDG] closely mirror those contained in [GWTW].’”

“Our own review of the two works reveals substantial use of GWTW… . TWDG copies, often in wholesale fashion, the descriptions and histories of these fictional characters and places from GWTW, as well as their relationships and interactions with one another… . After carefully comparing the two works, we agree with the district court that, particularly in its first half, TWDG is largely ‘an encapsulation of [GWTW] [that] exploit[s] its copyrighted characters, story lines, and settings as the palette for the new story.’

“Houghton Mifflin argues that there is no substantial similarity between TWDG and GWTW because the retelling of the story is an inversion of GWTW: the characters, places, and events lifted from GWTW are often cast in a different light, strong characters from the original are depicted as weak (and vice-versa) in the new work, the institutions and values romanticized in GWTW are exposed as corrupt in TWDG. While we agree with Houghton Mifflin that the characters, settings, and plot taken from GWTW are vested with a new significance when viewed through the character of Cynara in TWDG, it does not change the fact that they are the very same copyrighted characters, settings, and plot.” (Bracketed abbreviations and other content in the above three paragraphs are copied here verbatim from Appeals Court decision.)

The Court examined the parody defense:

“The fact that parody by definition must borrow elements from an existing work, however, does not mean that every parody is shielded from a claim of copyright infringement as a fair use… . For purposes of our fair-use analysis, we will treat a work as a parody if its aim is to comment upon or criticize a prior work by appropriating elements of the original in creating a new artistic, as opposed to scholarly or journalistic, work. Under this definition, the parodic character of TWDG is clear. TWDG is not a general commentary upon the Civil-War-era American South, but a specific criticism of and rejoinder to the depiction of slavery and the relationships between blacks and whites in GWTW. The fact that Randall chose to convey her criticisms of GWTW through a work of fiction, which she contends is a more powerful vehicle for her message than a scholarly article, does not, in and of itself, deprive TWDG of fair-use protection.”

If this was to be permissible parody, the Court should expect to find how the new work was “transformative” (using this term with the meaning given it by the Supreme Court in the Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. [“2 Live Crew”] decision): “The issue of transformation is a double-edged sword in this case. On the one hand, the story of Cynara and her perception of the events in TWDG certainly adds new ‘expression, meaning, [and] message’ to GWTW. From another perspective, however, TWDG’s success as a pure work of fiction depends heavily on copyrighted elements appropriated from GWTW to carry its own plot forward… .

“TWDG is more than an abstract, pure fictional work. It is principally and purposefully a critical statement that seeks to rebut and destroy the perspective, judgments, and mythology of GWTW. Randall’s literary goal is to explode the romantic, idealized portrait of the antebellum South during and after the Civil War. In the world of GWTW, the white characters comprise a noble aristocracy whose idyllic existence is upset only by the intrusion of Yankee soldiers, and, eventually, by the liberation of the black slaves. Through her characters as well as through direct narration, Mitchell describes how both blacks and whites were purportedly better off in the days of slavery… Randall’s work flips GWTW’s traditional race roles, portrays powerful whites as stupid or feckless, and generally sets out to demystify GWTW and strip the romanticism from Mitchell’s specific account of this period of our history. Approximately the last half of TWDG tells a completely new story that, although involving characters based on GWTW characters, features plot elements found nowhere within the covers of GWTW… . In TWDG, nearly every black character is given some redeeming quality — whether depth, wit, cunning, beauty, strength, or courage — that their GWTW analogues lacked.

“In light of this, we find it difficult to conclude that Randall simply tried to ‘avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh.’ It is hard to imagine how Randall could have specifically criticized GWTW without depending heavily upon copyrighted elements of that book. A parody is a work that seeks to comment upon or criticize another work by appropriating elements of the original… . Thus, Randall has fully employed those conscripted elements from GWTW to make war against it. Her work, TWDG, reflects transformative value because it ‘can provide social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one.’” (Inner quotes from Campbell)

The Appeals Court considered whether the new work copied too much. “Once enough has been taken to ‘conjure up’ the original in the minds of the readership, any further taking must specifically serve the new work’s parodic aims… . Houghton Mifflin argues that… a large number of characters had to be taken from GWTW because each represents a different ideal or stereotype that requires commentary, and that the work as a whole could not be adequately commented upon without revisiting substantial portions of the plot, including its most famous scenes… . We have already determined that TWDG is a parody, but not every parody is a fair use. SunTrust contends that TWDG, at least at the margins, takes more of the protected elements of GWTW than was necessary to serve a parodic function.” The Court later notes, “A use does not necessarily become infringing the moment it does more than simply conjure up another work.”

“SunTrust argues that TWDG goes beyond commentary on the occurrence itself, appropriating such nonrelevant details as the fact that the [Tarleton] twins had red hair and were killed at Gettysburg. There are several other scenes from GWTW, such as the incident in which Scarlett threw a vase at Ashley while Rhett was hidden on the couch, that are retold or alluded to without serving any apparent parodic purpose. Similar taking of the descriptions of characters and the minor details of their histories and interactions that arguably are not essential to the parodic purpose of the work recur throughout.” After listing many, the Court admits that “we are reminded that literary relevance is a highly subjective analysis ill-suited for judicial inquiry.”

On the entirely separate matter of financial impact, the Court considers: “The final fair-use factor requires us to consider the effect that the publication of TWDG will have on the market for or value of SunTrust’s copyright in GWTW, including the potential harm it may cause to the market for derivative works based on GWTW… . SunTrust proffered evidence in the district court of the value of its copyright in GWTW. Several derivative works of GWTW have been authorized, including the famous movie of the same name and a book titled Scarlett: The Sequel [1991, adapted into television movie 1994]. GWTW and the derivative works based upon it have generated millions of dollars for the copyright holders. SunTrust has negotiated an agreement with St. Martin’s Press permitting it to produce another derivative work based on GWTW, a privilege for which St. Martin’s paid ‘well into seven figures.’ Part of this agreement was that SunTrust would not authorize any other derivative works prior to the publication of St. Martin’s book.” Although one could argue that an unauthorized book once read might exhaust or satiate reader interest against further continuations of the original, the Appeals Court here, in deciding “on market substitution”, surprisingly said that the evidence “demonstrates why Randall’s book is unlikely to displace sales of GWTW. Thus, we conclude, based on the current record, that SunTrust’s evidence falls far short of establishing that TWDG or others like it will act as market substitutes for GWTW or will significantly harm its derivatives.” (The full decision does not elaborate.)

“We reject the district court’s conclusion that SunTrust has established its likelihood of success on the merits. To the contrary, based upon our analysis of the fair use factors we find, at this juncture, TWDG is entitled to a fair-use defense.” Also: “To the extent that SunTrust will suffer monetary harm from the infringement of its copyright, harms that may be remedied through the award of monetary damages are not considered ‘irreparable.’… In this case, we have found that to the extent SunTrust suffers injury from TWDG’s putative infringement of its copyright in GWTW, such harm can adequately be remedied through an award of monetary damages.”

Murray Hill Publications, Inc., vs Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation

USCA, 6th Cir (3-19-2004) ¤ 361 F.3d 312, 70 U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA) 1220, CCH 28,777

Two or more screenwriters can have the same experience and decide to write a script about it. Where both writers have contact with the same movie studio, the resulting movie can seem to have favored one writer by cheating the other. A lower court found in favor of the excluded writer, whereas the appeals court weighed facts ignored by the lower court to reach a verdict in favor of the studio.

Murray Hill Publications, Inc. initially won judgment against Twentieth Century Fox (TCF) for the movie Jingle All The Way (1996) which the lower court found infringed the submitted screenplay “Could This Be Christmas.”

The principal author of the Jingle All The Way screenplay was Randy Kornfield, a Fox script reader and freelance writer of screenplays, who was inspired by his difficulties buying a toy for his son and conversations with other parents similarly engaged. On January 11, 1994, Kornfield registered his “treatment,” a six-page summary of a proposed screenplay, then called “A Christmas Hunt,” with the Writer’s Guild of America. “On July 17, he registered a fleshed-out screenplay of this treatment. Executives at the Fox Searchlight division liked the screenplay and bought it for ‘1492 Pictures,’ a production company affiliated with Fox.”

The author of the “Could This Be Christmas” screenplay was Brian Webster, a Detroit school teacher and aspiring script writer who in 1988, inspired by his difficulties in obtaining a particular Christmas present for his son, wrote the first draft of his screenplay. “Webster first registered this screenplay with the Copyright Office in 1989 and re-registered it in 1991. From 1989 through 1993, Webster and his agent made repeated attempts to sell this screenplay to a variety of potential producers. While Murray Hill pleaded a number of theories on how the screenplay could have found its way to Fox during this period, the district court considered all of the theories too speculative and found that Fox did not have access to the Could This Be Christmas screenplay during this period. Murray Hill does not raise this issue on appeal. Significantly, on February 4, 1994, Webster sold an option to Could This Be Christmas to Murray Hill and eventually transferred all rights in Could This Be Christmas to Murray Hill. On June 21, Murray Hill submitted Could This Be Christmas to the Family Film division of Fox. On July 9, the Could This Be Christmas screenplay was read and summarized by Rudy Romero, another Fox script reader and friend of Kornfield’s. Romero was also the script reader who a few months later performed the same task for the Jingle All The Way screenplay. On August 1, Fox declined the Could This Be Christmas screenplay. After Fox declined the screenplay, Murray Hill made no further attempts to sell it.”

“While [the] complaint [judged in district court] alleged a multitude of theories of liability, the only claim still relevant is Murray Hill’s allegation that the Jingle All The Way movie infringed upon the copyright of the Could This Be Christmas screenplay. The court made a finding that Murray Hill failed to establish directly that Fox had access to the Could This Be Christmas screenplay at any time before Murray Hill submitted it to Fox. The case then proceeded to trial by jury. The district court instructed the jury based on the Ninth Circuit’s test for judging the ‘substantial similarity’ of copyrighted works. As the jury was deliberating, the court found that the Jingle All The Way treatment, created prior to the Could This Be Christmas submission, did not infringe on the Could This Be Christmas screenplay. However, the jury was not informed of this ruling. Four days later, the jury rendered a verdict in favor of Murray Hill. The damages included $1 million in producer’s fees and $500,000 in writer’s fees […], $2 million in lost goodwill, and $500,000 in merchandising revenue”.

“The Could This Be Christmas screenplay was copyrighted. Fox did have access to the Could This Be Christmas screenplay before it registered the Jingle All The Way screenplay and before production of the Jingle All The Way movie, but not before it received the Jingle All The Way ‘treatment.’…

“However, even a superficial glance at the Could This Be Christmas screenplay and the Jingle All The Way treatment reveals that whatever the similarities, they most certainly do not approach the level precluding all possibilities but copying. Therefore, the district court rightly found that the treatment was an independent creation.”

Of 24 similarities between the Could This Be Christmas screenplay and the finished Jingle All The Way movie, six were not in the treatment and thus added after exposure to the Could This Be Christmas screenplay.

The Appeals Court decided:

“Therefore, we hold that elements of a copyright defendant’s work that were created prior to access to a plaintiff’s work are to be filtered out at the first stage of substantial-similarity analysis, just as non-protectible elements are. In the present case, no reasonable jury could have found substantial similarity solely on the basis of the six minor elements not so filtered. Therefore, Fox’s motion for judgment as a matter of law should have been granted.

“For the foregoing reasons, we REVERSE the judgment of the district court and REMAND for an entry of judgment as a matter of law in favor of Fox.”

Cases Summarized in Other Sections |

| Ossip Dymow

vs Guy Bolton, et al. (launch this) was a lawsuit over alleged infringement where in fact only the basic idea was shared. Shirley Booth vs Colgate-Palmolive Company and Ted Bates & Co. (launch this) had a sitcom star suing when her general appearance and mannerisms were copied by the cartoon spokes-character in a commercial. Kalem Co. vs Harper Bros (launch this) had a silent movie declared an infringement of a book although the movie did not use any words from the book. Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc., et al. vs Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., et al. (launch this) discusses the Court’s decision as to similarities between the “Kandy Tooth” episode of the radio series Adventures of Sam Spade and the first Dashiell Hammett story about Sam Spade, The Maltese Falcon, on which radio rights were sold to a different company. |

Other Information

“A story has a linear dimension: it begins, continues, and ends. If a defendant copies substantial portions of a plaintiff’s sequence of events, he does not escape infringement by adding original episodes somewhere along the line.” Warner Bros. v. ABC, 720 F.2d 231, 241 (2d Cir. 1983).

13A.1 similarity: subconsciously created

What the Courts Ruled

Bright Tunes Music Corp. vs Harrisongs Music Ltd, et al

USDC SDNY (9-1-1976) ¤ 420 F.Supp. 177

Bright Tunes owns copyright to the song “He’s So Fine,” recorded by the Chiffons, after being written in 1962 by Ronald Mack. George Harrison was credited with writing “My Sweet Lord” in 1970. (Billy Preston worked on it too, though Harrison is solely credited on the copyright registration.) The Court held: “The harmonies of both songs are identical.” As Harrison was so creative and successful that he shouldn’t be expected to infringe, how could this happen?

In 1963, “He’s So Fine” was at the top of the charts for seven weeks in England, where the Beatles (of which Harrison was part) were also top sellers. As part of the same business, Harrison surely knew the song.

“It is apparent from the extreme colloquy between the court and Harrison covering forty pages in the transcript that neither Harrison nor Preston were conscious of the fact that they were utilizing the ‘He’s So Fine’ theme. However, they in fact were, for it is obvious to the listener that in musical terms, the two songs are virtually identical except for one phrase.”

The testimony reported how “My Sweet Lord” took shape a little at a time. The Court reasoned: “As he tried this possibility and that, there came to the surface in his mind a particular combination that pleased him as being one he felt would be appealing to a prospective listener … Why? Because his subconscious knew it already had worked in a song his conscious mind did not remember… . Harrison had access to ‘He’s So Fine.’ This is, under the law, infringement of copyright, and is no less so even though subconsciously accomplished.”

13A.2 similarity: different markets

Where to Look in the Law

1909 Act: Not mentioned

1947 Act: Not mentioned

1976 Act: §107(4)

What the Courts Ruled

Time Incorporated vs Bernard Geis Associates, et al.

USCD S.D.N.Y. (9-24-1969) ¤ 159 USPQ 663

The only motion pictures of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy were filmed by amateur photographer Abraham Zapruder. Life magazine purchased the rights to the film for $150,000 and quickly put out an issue reproducing frames from that film. Time-Life (parent company of the magazine, and also known as Time Incorporated) has thereafter published or leased reproduction of frames and footage from this film to other companies.

The author of a non-fiction book titled Six Seconds in Dallas bypassed the use of actual images of the assassination in his book. Instead, to illustrate the moment of death by images which appear within this book about the event, the author chose instead to publish line drawings showing the key moments. The author admitted that these were drawn with eyes on the actual images in the Zapruder film. Time-Life sued for infringement of copyright.

The author of a non-fiction book titled Six Seconds in Dallas bypassed the use of actual images of the assassination in his book. Instead, to illustrate the moment of death by images which appear within this book about the event, the author chose instead to publish line drawings showing the key moments. The author admitted that these were drawn with eyes on the actual images in the Zapruder film. Time-Life sued for infringement of copyright.

The court ruled: “A news event [the death of President Kennedy] may not be copyrighted… [yet] Life claims no copyright in the news element of the event but only in the particular form of record made by Zapruder… .” Zapruder’s motion pictures of that event were deemed copyrightable.

“Any photograph reflects ‘the personal influence of the author, and no two will be absolutely alike,’ to use the words of Judge Lerned Hand.

“The Zapruder pictures in fact have many have many elements of creativity. Among other things, Zapruder selected the kind of camera (movie, not snapshot), the kind of film (color), the kind of lens (telephoto), the area in which the pictures were to be taken,…, and (after testing several sites) the spot on which the camera would be operated.”

On the basis of the selectivity exercised by the photographer, the images can be said to be copyrightable. However, because the book uses sketches rather than the photographs, the question remained as to whether they were infringements.

The court wrote that the book “has a number of what are called ‘sketches’ but which are in fact copies of parts of the Zapruder film.” Even so, the court was not convinced that the dissemination of the sketches interfered with the profits of Time Incorporated.

“There is public interest in having the fullest information available on the murder of President Kennedy. Thompson did serious work on the subject… The book is not bought because it contained the Zapruder pictures [but] because of [Thompson]’s theory. There seems little, if any, injury to plaintiff… . There is no competition between plaintiff and defendant.”

(The case gets convoluted as to permissions received. Some sketches appeared in an issue of the Saturday Evening Post as illustrations to an article that led to the book. The artist was paid $1550 to “make copies in charcoal by means of a ‘rendering’ or ‘sketch.’” The permissions involved in the Saturday Evening Post publication differed from that sought for the book, with seemingly conflicting testimony as to what was granted by Time.)

illustration: President John F. Kennedy in a portrait dated July 11, 1963, shot by a White House photographer.

Cases Summarized in Other Sections |

| Howard Loeb vs A.L. Turner and Trinity Broadcasting Corporation (launch this) mentions that where the same content was broadcast on radio stations a thousand miles apart, the supposed-infringing station was not competing in the same market. |

The Copyright Registration and Renewal Information Chart and Web Site

© 2007 David P. Hayes

“Indeed, it seems to be that — putting the case more favorably for the plaintiff than a comparison of the works here justifies — the most that can be said for them is that they brought this suit for literary larceny because they were infected with the fallacy, which seems to be endemic among writers, that copyright may be claimed on a theme or an idea, which, of course, is not and never has been the law.” The similarity involved little more than each work being about a modern American finding himself transported to Ancient Rome, where the bulk of the story takes place.

“Indeed, it seems to be that — putting the case more favorably for the plaintiff than a comparison of the works here justifies — the most that can be said for them is that they brought this suit for literary larceny because they were infected with the fallacy, which seems to be endemic among writers, that copyright may be claimed on a theme or an idea, which, of course, is not and never has been the law.” The similarity involved little more than each work being about a modern American finding himself transported to Ancient Rome, where the bulk of the story takes place. James H. Collins was well-known as a test pilot and his death on March 22, 1935, in an airplane accident was news. A book assembled by his widow from his writings was titled Test Pilot and was copyrighted September 16, 1935, but it sold fewer than 10,000 copies. MGM had announced a movie to be titled Test Pilot on January 14, 1933 (verified from the Hollywood Reporter) but delayed production. On the basis of an examination of the book and a cutting continuity of the movie, the Court determined that the similarities were in the title and incidental material which should be expected when writing about the same profession. MGM had not infringed.

James H. Collins was well-known as a test pilot and his death on March 22, 1935, in an airplane accident was news. A book assembled by his widow from his writings was titled Test Pilot and was copyrighted September 16, 1935, but it sold fewer than 10,000 copies. MGM had announced a movie to be titled Test Pilot on January 14, 1933 (verified from the Hollywood Reporter) but delayed production. On the basis of an examination of the book and a cutting continuity of the movie, the Court determined that the similarities were in the title and incidental material which should be expected when writing about the same profession. MGM had not infringed.